You are asked to hire someone who can help your sponsor win an election.

Your sponsor has expressed a concern that "political lobbying is the next big scandal waiting to happen" - you may want to include that in your risk assessment.

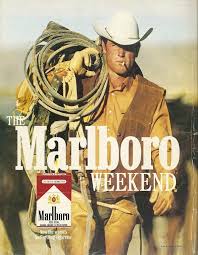

Your sponsors policies are also linked with reducing long term health costs. They recognise obesity, too much alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking have a detrimental impact on the electorates' health and also on the (excuse the unfortunate choice of words here) the whole life costs of running the health service. Future health costs are one of the dominant causes of politicians insomnia.

The preferred provider has a proven pedigree of being associated with electoral victories, of course that is no indication of 'cause and and effect', nevertheless it is better than always being associated with losers. The provider also has a risk if your sponsor turns out to lose.

Your preferred provider naturally enough is in the business of influencing - the trinity of steering the electorate, steering policy, and in steering big business. That unholy alliance may just have some ever so slight link with lobbying.

Given the health policy and risk of perceived lobbying, it may be clever to ask the potential provider if they have any perceived conflicts of interest. Of course you need to be very sceptical about any answers, after all, the provider's core business is getting people to make the decisions the provider wants them to make and be distracted from any thing which may have not get them to 'yes'.

Given all that due diligence, you appoint the preferred provider (did you really have a choice or was it a forgone conclusion).

This morning you were relaxing over breakfast, watching yet more depressing news coverage of sectarian violence in Belfast (wasn't that all supposed to be sorted by Blair) - having said that, thankfully there's nothing today about public procurement. You glance at The Times: "Heavens to Murgatroyd" your procurement recommendation is all over the front page, the second page, and even the Leading Articles (bizarrely but thnakfully now tucked away on page 24). Turns out there was a perceived conflict of interest - others think there's a connection between your provider, who happens to also be a consultant to the tobacco industry and a U-turn on an initiative to reduce smoking - are they mad, how on earth could anyone draw that conclusion.

Forget cutting the grass, you need to cut the LinkedIn profile and the section which said 'procured special electoral adviser'. You've just fired up your Mac to make that minor deletion, when your landline and mobile phone go simultaneously, one caller is FM and the other GO, as if twins on Big Brother, both say

"Wasn't it your job to minimise exposure to risk? Is the provider paid by outcomes? Were you lobbied into making that recommendation?"

After the brief calls, you start to consider this week's shopping and the visit to the local food bank - a Marloboro weekend?